Why You Should Read the Classics This Summer

By Evie Solheim

Many of us make it a goal to read more once summer arrives – after all, what’s more pleasant than sitting in the sun with a good book? But if you’re looking for a little inspiration for your summer reading list, don’t forget about the classics. These books may not be topping the bestseller lists right now or taking #BookTok by storm, but they’ll be stories that stay with you long after summer is gone.

One question you may have before diving into classic literature is: what are the classics? To get some help understanding what “classic” means, I reached out to Nadya Williams, writer and book review editor for Current.

“There are multiple uses of these terms,” Williams tells The Conservateur. “All my degrees are in the field of ‘Classics,’ which is the umbrella term used to describe the study of all things related to Ancient Greece and Rome.”

But the definition of “classic literature” is one that has continued to change over time, she explains.

“It seems that most people use the terms ‘classics’ or ‘classic literature’ today to refer to anything that we might consider highbrow(ish),” Williams says. “Shakespeare was sort of mainstream in his day, whereas we consider him a true classic. Or, I remember my high school French teacher being shocked that I was reading the French author Colette in college French lit classes – as she put it, Colette was not considered classic enough to be respectable college reading when she was in university! And, to come back full circle to the Greeks and Romans, we see all of them as ‘classics,’ even as in antiquity, there was a definite hierarchy of which authors were considered more respectable than others.”

Ultimately, adding the descriptor “classic” to a work of literature is always a positive thing, Williams says.

Reading classic authors doesn’t mean you’ll only be reading self-serious novels with self-serious themes. Chris McCaffery, managing editor of the Washington Review of Books, emphasized the enjoyment of reading classics in an interview with The Conservateur.

“I always want to insist that whatever else you get out of reading the classics – and these can be big serious ideas, because I think it’s a law of cultural tastemaking that the works of art that really endure do so because they disclose something really intimate about the joys and tragedies of our lives – whatever gravity you want to bring to your reading needs to be balanced by being ready to laugh, and laugh a lot,” McCaffery says.

Just because a work of literature isn’t on any lists of “100 Classics You Must Read Before You Die” (yes, such things exist) doesn’t mean it isn’t worth your time, he adds.

“There are a lot of minor classics that I think are wonderful, too,” McCaffery says. “The Lais of Marie de France; George Meredith’s Modern Love sonnets; Pnin, the really funny and touching stories [Vladimir] Nabokov wrote for The New Yorker in the ‘50s; Excellent Women [by Barbara Pym] of course.”

Human Nature Hasn’t Changed Since Homer

Perhaps the most transcendent part of reading a book from hundreds or even thousands of years ago is recognizing yourself in the characters. After all, human nature hasn’t changed since the ancients first began recording narratives.

“Technology changes, but the human experience more broadly doesn’t: we still long for beauty, we desire relationships, we love our spouses and children, we mourn over pain and suffering,” Williams says. “Good literature from the past bridges the time gap and makes us feel the same emotions that a reader 2,000-plus years removed may have felt, and that is just so beautiful!”

One of Williams’ favorite classic reads – that’s small enough to fit in a beach bag – is The Golden Ass by Apuleius, the only ancient novel written in Latin that has survived in its entirety.

“It’s fabulously crazy and unexpected – a man goes on vacation and gets accidentally turned into a donkey! It was the inspiration for C.S. Lewis’ stunning novel Till We Have Faces, so might as well take both to the beach. Apuleius will make you laugh, while Lewis will make you weep,” she says.

One thing you might notice about classic works is that their authors wrote in a variety of languages – some of which, like Latin, are now considered dead. For most well-known works, there are many translations to choose from, but not all translations are equally faithful or helpful at giving context.

“A lot of good modern translations (e.g., in the Penguin Classics series) have a short introduction that provides a historical orientation to the text and allows you to know what to expect,” Williams says. “But also, different genres were written for different purposes, and even classic novels have always been meant to be bingeable – therefore, easier reads than, say, Thucydides, whom I positively adore, but even I might not take him to the beach (sorry, old friend!).”

Learn to Speak the “Language” of the Classics

Familiarity with classic literature is its own language – you’ll start to see connections everywhere once you “speak” it. Many of us know that popular films like Clueless and O Brother, Where Art Thou? are loose retellings of classics (Jane Austen’s Emma and Homer’s The Odyssey, respectively). Such references aren’t always so overt but are often just as meaningful. Take, for example, the 2007 film Atonement. Protagonist Briony Tallis, feeling remorse over something she did as a child, scrubs and scrubs her hands – a detail that may not mean much to viewers until they connect it to guilty Lady Macbeth washing her hands in Shakespeare’s Scottish play.

Knowledge of classic literature is applicable across many fields, says Philip D. Bunn, who is the Lyceum Visiting Scholar at the Clemson Institute for the Study of Capitalism. He also writes about what he reads in his newsletter Everything Was Beautiful.

Students who enjoy reading widely and are familiar with classic texts tend to get the most out of the classes on political thought he teaches, he says.

“You can’t, for example, really grasp Plato if you don’t have some background reading Homer. You can’t really catch some of the allusions and arguments made by the Founding Fathers, for example, if you aren’t versed in Shakespeare and the Bible,” Bunn explains. “The classics form a kind of common script, a language we can use for examples and symbols to make our communication more effective and deeper, and so these things sort of build on each other. Once you read Homer, you will see him everywhere. Once you read Plato, you will see him everywhere. Once you read Shakespeare, you will see him everywhere.”

Reading Is Social

This point may seem counterintuitive because reading is an activity for one, right? But once you read a really good book, you’re going to want to talk about it with anyone else who’s read it, too.

“Another thing that makes a book a classic is that we’ve never run out of things to say about them,” McCaffery says. “I think of literature almost as a shared history you can have with many people, in the same way shared experience brings friends closer to one another and can continue to be a topic of discussion and argument. With a classic work you’re looking at a great mystery, and that’s something you can’t understand until you start talking to people about it. Reading isn’t a complete experience – I’d almost say you shouldn’t say you’ve read a book at all – unless you’ve really talked about it with a friend, or made a friend by talking about it.”

Enter the book club. Yes, hosting a book club is a great excuse to eat yummy snacks and chit-chat with friends, but it can also facilitate discussions that your group would otherwise never have. And, this reason to read classics may not be very romantic, but they can be much cheaper than brand-new bestsellers ($1 at the used book store versus $26 on Amazon? With #Bidenflation, the choice is easy!).

I’m currently in a book club that’s reading easily accessible classics and it’s been a really great way to fill in the gaps in my classics knowledge. Plus, many of us in the book club are moms with young kids, so we love being able to find free audiobook versions of whatever classic works we’re reading. I’m a big fan of the Libby app, which connects to your library card to bring you free audiobooks and ebooks.

There are tons of online reading communities you can plug into, too. The Literary Life Podcast focuses on classic works and boasts more than 9,000 members in its Facebook discussion group. On the podcast What Should I Read Next?, host Anne Bogel mixes classic recommendations in with contemporary reads. Bogel frequently interviews her own audience members on the show to help them decide, well, what to read next!

Evie’s Reading Suggestions

Now that you’re interested in adding a classic novel or two to your summer reading list, allow me to share a few titles that may pique your interest. One of the saddest realizations in life is that you’ll never be able to read all the books you want to read – but that doesn’t mean you can’t try.

Here are a few reading suggestions based on your favorite genre:

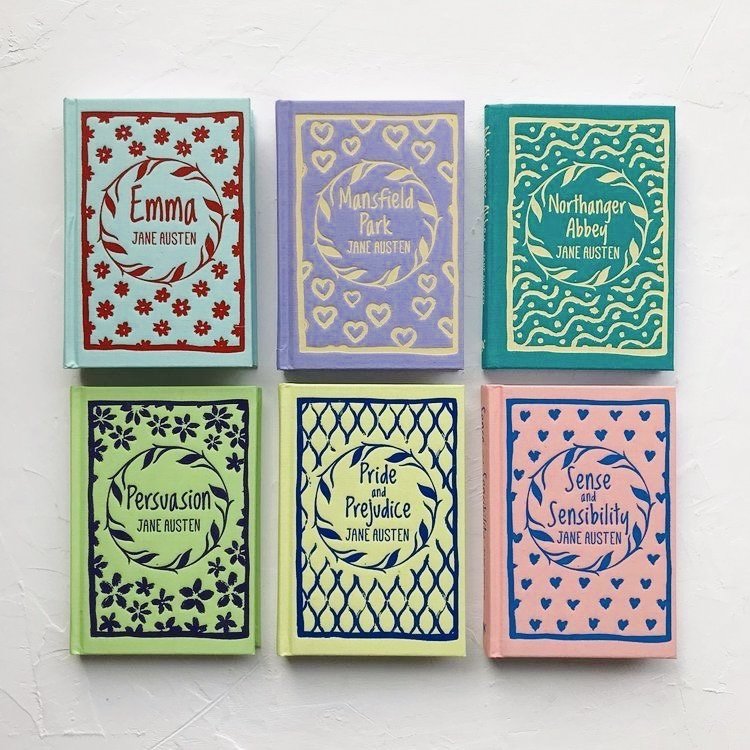

If you like romance: Emma by Jane Austen

If you like coming-of-age: The Adventures of Augie March by Saul Bellow

If you like dystopian: Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

If you like epics: Beowulf translated by Seamus Haney

If you like horror: Great Tales of Horror by H.P. Lovecraft

If you like fantasy: The Light Princess by George MacDonald

If you like comedy: A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

If you like surrealism: One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Evie Solheim is a freelance journalist and author of The Girl’s Guide, a biweekly newsletter that features dating and career advice, interviews with interesting women, and more. She and her family live in West Virginia.